Access to clean water has shaped human settlements throughout history. Melbourne is no different. As it grew from a small colony on the Yarra River into a major city, new water sources were added to meet demand.

1800s: The early years

For tens of thousands of years, Aboriginal people relied on rivers and creeks or dug wells to get water from underground. The first Europeans also took water from creeks, but this soon changed as the population grew. Some of the infrastructure and policies from this period still serve us today.

1835: Settlement begins

In Melbourne’s first 22 years, most houses were built near the Yarra River. People collected water from natural falls upstream of where Queens Bridge is today.

As the town grew, people had to travel further. Carts began selling water door-to-door for three shillings a barrel (about 30 cents for 550 litres). The price was expensive, despite the poor water quality.

1857: Melbourne’s first reservoir

The 1850s gold rush transformed Melbourne into a major city. But more people meant more pollution from sewage, tanneries and other industries. This flowed into the river (whose water became known as ‘Yarra Soup’), spreading diseases like typhoid – called ‘colonial fever’.

To address this, ex-convict James Blackburn suggested building a reservoir at Yan Yean. When completed in 1857 it was the world’s largest artificial reservoir.

Did you know: While the reservoir was being built, an iron tower was erected in the city to store water from the Yarra River. It was later moved brick by brick to the Western Treatment Plant, where it stands today.

1880s: Catchment protection begins

The government bought more than 100,000 acres (400km2) of land next to rivers and reservoirs. This protected them from human activity, ensuring high-quality drinking water into the future.

Today, Melbourne is one of only a few cities in the world with protected water catchments.

1890s: Population hits half a million

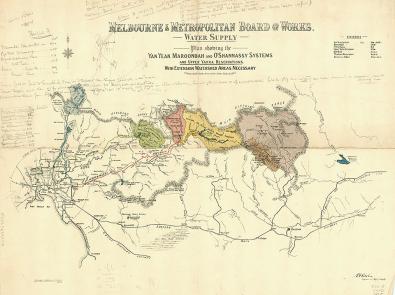

The Watts River near Healesville was diverted to supply water (via the Maroondah Aqueduct) to Melbourne – then a city of half a million people.

To look after the city’s water and sewerage, the Melbourne and Metropolitan Board of Works was formed in 1891.

1900s: Rapid growth

Melbourne’s growth continued into the 20th century. Several major dams were built to meet demand for water – and tested by periodic droughts.

1920s & 30s: Major public works program

A large-scale dam construction program began. It addressed problems with water quality and pressure in the eastern suburbs – and the need to create jobs during the Great Depression.

This saw three reservoirs completed:

- Maroondah (1927)

- O’Shannassy (1928)

- Silvan (1932).

These boosted storage capacity from 30,000 million to 104,500 million litres.

1940s & 50s: Post-war pressures

A very dry summer brought water restrictions to Melbourne in 1937-38, and again in 1945-46. Rapid population growth and immigration after World War II only intensified the need for more water.

After delays from the war, construction restarted on Upper Yarra Reservoir in 1946. It was completed in 1957, and tripled our water storage capacity to almost 300,000 million litres.

1960s & 70s: Planning for growth

1973: Fluoride for stronger teeth

Australia recognised the benefits of adding fluoride to water to prevent tooth decay. Under a new Victorian Government health policy, local fluoridation plants were built to fluoridate all public water supplies.

1984: Thomson – our biggest reservoir yet

Sugarloaf Reservoir was completed in 1981. It added 95,000 million litres to Melbourne’s water storage capacity.

But there were still concerns about drought, and so the Thomson Reservoir was built. Connected to the water network in 1984, right after another drought in 1982-83, it couldn’t have come at a better time.

That year, the ‘Don’t be a Wally with Water’ advertising campaign changed attitudes to wasting water. It became compulsory for all new toilets to be dual flush.

1991-95: Major changes to our water industry

The Melbourne and Metropolitan Board of Works merged with several smaller urban water authorities. Melbourne Water was formed, and began operating in 1995 as Melbourne’s wholesale water company.

2000s: Towards a water-smart city

A new century ushered in the worst drought on record. Alternative water supplies were added, and water conservation entered the public consciousness.

1996-2010: Millennium Drought hits hard

In 1997, the amount of water entering reservoirs suddenly dropped by two-thirds compared to the previous year. This marked the start of the Millennium Drought.

Stage 1 water restrictions started in 2006, when storages were nearly half empty. Within a year, restrictions had increased to Stage 3a.

In 2008 the ‘Target 155’ program began encouraging each person to limit their water use to 155 litres per day. Melburnians responded, using 22% less water compared to the 1990s.

2009: Storages reach an all-time low

In February, the ‘Black Saturday’ bushfires damaged about 30% of Melbourne’s water supply catchments. The bad news continued, with water storages falling to 25.5% in June. This was the lowest they’d been since the Thomson Reservoir began filling in 1984.

Thankfully, Tarago Reservoir was reconnected to the water supply network on 24 June. This increased Melbourne’s total storage capacity by 37,500 million litres.

2010: North-South Pipeline completed

The North-South (or Sugarloaf) Pipeline was built to boost Melbourne’s water supplies in times of critical need. The 70-kilometre pipe can carry water from the Goulburn River to Sugarloaf Reservoir, and is completely powered by hydroelectricity. It provided the largest single increase to our water storages in more than 25 years.

Water restrictions began easing, from Stage 3a to Stage 3 in April, and then to Stage 2 in September.

2012: Desalination diversifies water supplies

Water restrictions ended, replaced by permanent water saving rules. But the Millennium Drought showed the need for alternative water sources. A rainfall-independent desalination plant was completed the same year.

The plant tops up our water storages, creating a buffer against dry periods and drought. It produced its first order of desalinated water in 2017.

2015: Rainwater tanks become compulsory

One outcome of the Millennium Drought is making rainwater tanks compulsory in new homes. A case study shows that using them in the laundry, toilet and garden reduces reliance on municipal water by 40%.